In Melville’s 1967 seminal hitman film Le Samourai, Alain Delon’s extremely professional hitman follows a fictional code of honor that dictates his every move. He spends very little time performing hits and spends most of it wearily roaming the street of Paris, torn between dedication to the code and a desire to free himself of a witness’s potential testimony. Spoilers: the “samurai” follows his code and essentially commits suicide.

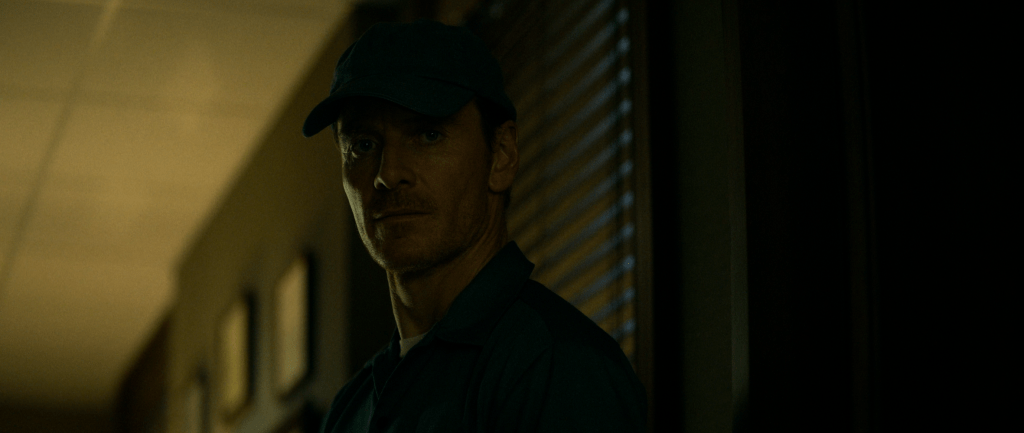

Contrast this to David Fincher’s 2023 version, whose code is quite literally “I don’t give a fuck.” The aptly named killer, played with neurotic perfection by Michael Fassbender, displays little concern for innocents and wears a marked disdain for empathy on his sleeve. Not to mention the fact that he listens exclusively to The Smiths. The lengthy opening scene, a stakeout that involves our hitman fumbling a hit for the first time, establishes a running narration that provides us an intimate, candid look into the killer’s head. We learn he is an almost comically misanthropic, nihilistic perfectionist who wishes to be completely detached from both society and humanity. In any other film, this character would be the bad guy’s second-in-command, played by your favorite B lister with weird tattoos. Or a teenage girl after a messy breakup.

The killer’s problem is that he can’t detach completely. After the missed hit leads to his girlfriend (wife? sister?) being beaten nearly to death, he sets out on a very personal revenge mission that involves systematically breaking every single rule he has ordained as he hunts down those responsible. “Only do what you are paid to do,” he instinctively repeats to himself while sneaking into a thug’s home. The killer cannot ignore the desire to keep his girlfriend safe, or the base thrill of revenge, even as it means murdering his boss and putting his own life and safety at constant risk. In the film’s best scene, the nearly mute assassin sits across from Tilda Swinton’s hitman character in a restaurant and listens intently to her claim that maybe, quite possibly, he wanted to kill them all anyway. Not much for conversation, he shoots her in the head.

While Le Samourai explored someone refusing to compromise to the world around him, Fincher’s hitman is forced to adapt. He makes mistakes, he operates on emotion. He becomes reactive and vulnerable. The film’s “climax” involves our killer finding out that his girlfriend’s attempted murder wasn’t personal at all. The wealthy businessman guilty of ordering the hit was offered the death of the killer’s family as an apology by the agency, which he casually accepted. Perhaps this is an American Psycho way of stating that the world around our sociopath isn’t as different as we thought. Did I mention the killer does yoga?

Curiously, the killer chooses not to kill the businessman. This action and the closing narration further develops these themes; initially “one of the few,” our protagonist now see himself as one of the many. That is, he recognizes his hypocrisy and inability to reject his innate humanity. The killer seemingly retires, no longer suitable for living up to his name. How fitting that Fincher’s face of moral superiority in the twenty first century is a sociopathic serial killing monster. 11-27-23

Leave a comment