Rest in peace, Christopher Nolan. You would have loved watching Denis Villeneuve’s magnificent and massive Dune: Part 2.

While I’m kidding, I do think Villeneuve has all but established himself as the superior blockbuster filmmaker right now. As compared amongst talking heads, this may be his Dark Knight, or even his Empire Strikes Back, according to Nolan himself. While it’s difficult to imagine the excitement and hype matching those cultural events, Dune: Part 2 is certainly comparable as combination of auteur craft and summer studio fare. This is Villeneuve’s fourth film in the sci-fi genre, and it seems like he’s only getting better at pairing large scale drama with intense personal repercussions.

That comparison is only here to establish just how good I think this movie is. Dune: Part Two is an extremely relevant beast, prescient to the upcoming election, but also really good sci-fi, and an excellent war movie, too. It’s also chock full of weird and dynamic characters who are given due focus and appropriate depth across the film’s near perfectly paced 2 hour and 46 minute runtime. While I definitely enjoyed the first film, the full benefits of Villeneuve’s decision to split the first book in two are now apparent. The lengthy exposition and convoluted world building of Part One is gone. With this one, Denis is having fun.

We catch back up to Paul Atreides (Timothee Chalamet) and his mother Lady Jessica (a freaking creepy Rebecca Ferguson) virtually right after the events of the first movie. Having joined the Fremen after the Atreides house was destroyed by the Harkonnen, we quickly learn that Jessica is fanning the flames of a rumor that Paul is the messiah foretold in an ancient prophecy. Jessica drinks worm poison and begins to have spiritual conversation with her unborn daughter, who pushes her to convince the Fremen of Paul’s role as liberator. The Fremen are reluctant to accept a foreigner as savior, but Chani (Zendaya), who Paul forms a romantic relationship with, gradually helps convince her group of Paul’s good intentions.

While wanting to help the Fremen, Paul primarily wants revenge against the Harkonnen for the death of his father – understandable if you watched the first film. But he begins to have visions and dreams of a future where a holy war incited by his own rise to power results in widespread famine and suffering. Comforted by Chani, Paul presses forward, indulging his mother’s attempts to build a religious myth around his name. As he wages war on the Harkonnen, his actions begin to trouble Emporer Shaddam (Christopher Walken), who is, like, king of the universe? This is based on hardcore sixties sci-fi, after all.

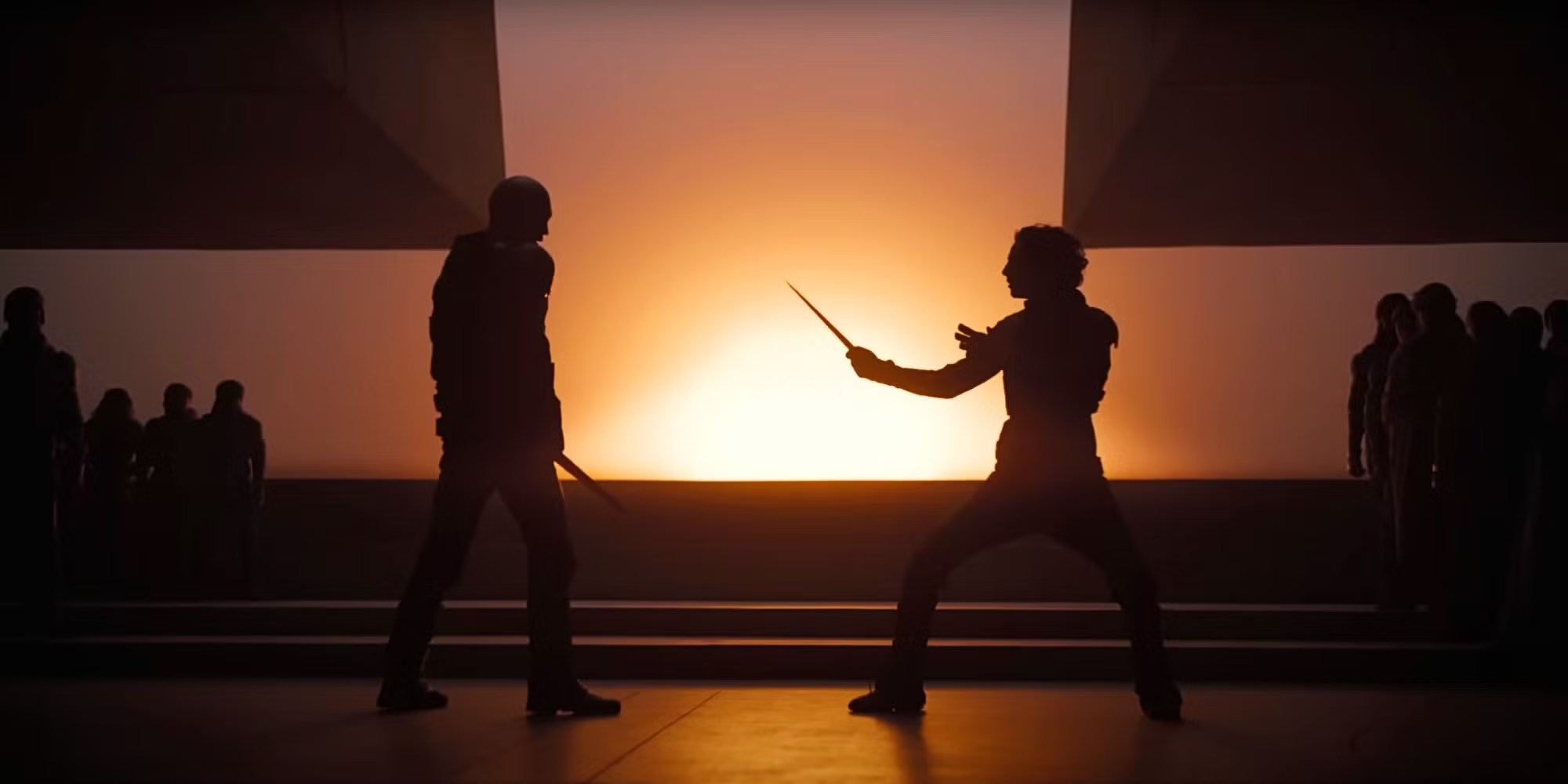

Paul eventually drinks the same worm poison that his mother has (“The Water of Life”) and sees different possibilities that the future holds. Conflicted, he realizes that the Harkonnen Baron is his grandfather, making him a part of the bloodline, too. He accepts the prophecy as true and embraces the religious messiah angle, leading the Fremen is a furious battle against the Harkonnen with giant worms and atomic warheads (sixties sci-fi), where it just so happens that the Emperor is visiting. Paul kills the Baron and then assumes leadership as the new Emperor after defeating the Baron’s psychotic nephew Feyd-Rautha in a vicious knife fight for the throne.

The dozens of shots of Jessica’s baby in utero reminded me of the Starchild from 2001: A Space Odyssey. In 2001, mankind transcends from primal apes to fully conscious and autonomous beings, but at the end, Bowman is reborn as a baby. One way to interpret this ending is that Bowman/humanity is still an infant compared to the intelligence and knowledge of the unseen aliens. Here, it’s interesting to see a literal embryo giving Lady Jessica orders on how to convince an entire culture to trust in a single man. It’s a accidental version of the Starchild that has skipped natural maturation and growth, born as an adult in a woman’s stomach and already pre-packaged with political influence.

Birth and rebirth is a recurring theme in Dune: Part Two. To become the prophesied Lisan al-Gaib, Paul must accept his visions coming true, betray his promises to Chani, and start the holy wars. After consuming the poison, he knows these things will happen if he follows through on leading the Fremen into battle. As he tells his mother, they will win by “becoming” Harkonnens – the monsters he wants revenge against so badly. Paul’s rebirth as messiah is both necessary and simultaneously a mistake, because like Achilles, Paul knows his fears will come true, and like all good politicians, he chooses the lesser of two evils. His simultaneous role of savior and harbinger of destruction also brings the themes of last year’s Oppenheimer to mind.

Political discourse is a concept baked into Dune, from the bickering between the various houses, the Emperor’s complete rule, and the constant meddling being performed by the Bene Gesserit, a group of witches who seemingly have complete control over the social, religious, and political spectrums. While Paul’s story initially mirrors Jesus, another interesting parallel lies in the modern political stage in America. Villeneuve used the border to probe in Sicario, and here he uses the Bible. Without naming any names, the idea of a wealthy elite who is “one of the good ones” taking control of the poor and oppressed through the promise of destroying the system is one we’ve recently seen in the real world. As Paul learns in Part Two, controlling the spice isn’t necessary, only convincing enough people that he is the chosen one. It’s also worth noting that the Fremen’s fanaticism isn’t without reason, or results. It’s just that, you know, this is the same guy who realizes his jihad will lead to the death of millions of innocents, and he’s cool with it if it kills the Baron. The theme of freeing one group only to oppress countless others is the narrative gasoline that fuels the bittersweet ending of Part Two. “Never underestimate the power of faith,” says the Emperor’s daughter, Irulan, who serves as something of a narrator.

Austin Butler’s Feyd Rautha, who still sounds like Elvis, serves as a dark reflection of Paul. While Atreides grapples with the moral implications of his destiny, Feyd embraces the ruthless path to power. I particularly enjoyed the running gag of the character simply slicing someone in the throat whenever he’s annoyed. Like Paul, Feyd was bred to be a political force, and the scene where he proves his worth through physical violence in the arena mirrors the end of the first film and Paul’s introduction into the Fremen. I also loved how, with countless lives and diplomatic implications at stake, things are settled with a simple knife fight. It’s all the more ironic given that Feyd is the obviously superior fighter and only loses after Paul feigns mortal injury.

At the end, Jessica is told by the former reverend mother that she, of all people, “should know that there are no sides.” Whether it be Feyd, or cousin Paul, or even someone else, figures promising salvation will always cross the line to get what they want, because that’s the essence of being human. Nearly every character in Dune ends up being out for themselves, with the exception of Chani. It’s fitting that instead of ending with our hero, who has ascended to God-like status and taken his sweet revenge, the closing shot is focused on his ex-girlfriend, angry and grieving at the sight of her lover becoming the new dictator of the universe. 03-02-24

Leave a comment