Clint Bentley’s Train Dreams is about the beauty of living for the sake of it. You may have heard it described by multiple outlets as “the best movie Terrence Malick never made.” While no one can make a stalk of wheat look quite as poetic as Terry, the comparison is not totally unearned. With Malick busy entering his sixth year of editing his upcoming biblical epic, Bentley’s film has arrived just in time to carry the flag for introspective spiritual meditation. It might be too slow for some viewers, but nearly everyone will recognize the humanity in Train Dreams as something we need a little more of.

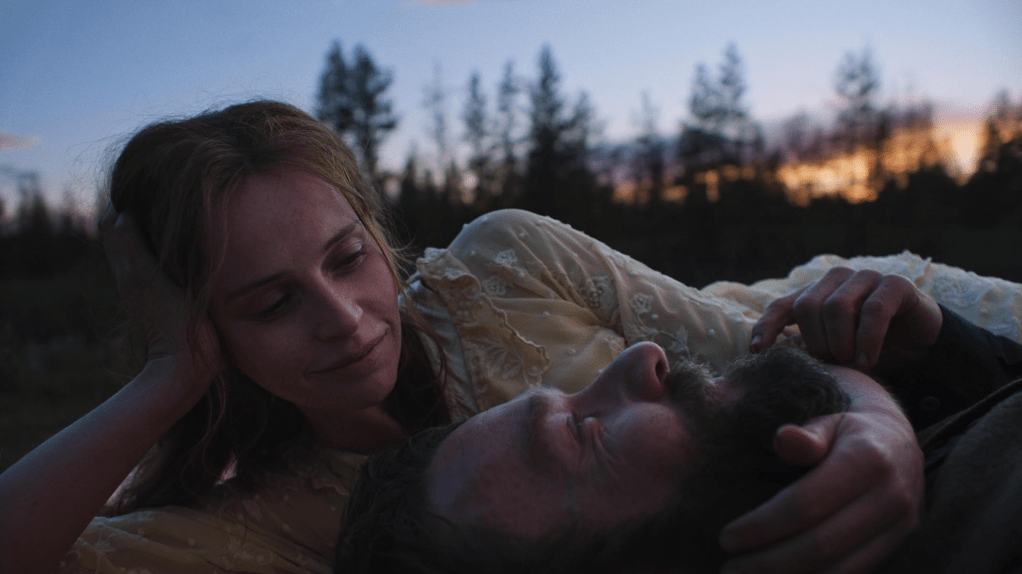

Set in the remote forests of early 20th-century Idaho, Bentley’s sophomore effort traces the hard, wandering life of Robert Grainier (Joel Edgerton), an orphan who finds love and builds a homestead. As he labors on railroads and in logging camps, the harshness of frontier work and the presence of strange dreams begin to haunt him. After his wife and child seemingly perish in a forest fire, Robert watches the world begin to pass him by as he struggles to keep going.

Bentley has unsurprisingly cited Malick (and specifically Days of Heaven) as an inspiration. However, another film he has referenced is Tarkovsky’s Andrei Rublev. One way to interpret that film is as a mythic exploration of the artist. Andrei experiences great suffering and tragedy but renews himself through creation, specifically painting. In addition to serving as a spiritual release for his confusion and despair, his art allows him to leave an indelible mark on the world, proof that he existed. Long after he is gone, thoughts and ideas that originate in his brain will endure through his paintings.

Train Dreams also operates within the register of myth, but across the American frontier. Grainier exemplifies the anonymity of the everyman. He is a hard-working, quiet, and loving husband and father whose impact on the world centers primarily on his wife and child. When they are taken from him, there is no one left to understand the depth of his loss except others suffering from the same affliction. The world is a mystery to Grainier because his very connection to it has been severed. He has no release, let alone legacy, and when he dies, his experience dies with him. Should that frighten us, or is there comfort in acknowledging the limits of our own subjective experience?

The fear being explored here isn’t the inability to understand the world, necessarily, but the complexities of your own mind. One of the film’s most memorable scenes shows several men huddled around a campfire, discussing the possibility of running out of trees to chop down. If we were to analogize the swift felling of a tree to the hopes and dreams of mankind in the face of grief, as the film invites us to do, we begin to understand its broader point: it can take an entire lifetime for something new to develop in the wake of destruction.

But change, of course, is the only constant in our lives. Grainier laments the passing of time but can’t help seeing beauty in the mundane or forging new connections. There is a predestined element to the film, from the anonymous narration that reminds us Grainier’s happiness will cease before we realize why, to the dreams that serve as portents of death. Living and dying are inexorably intertwined. There is also obvious symbolism in the trains that Grainier dreams of. Trains run on fixed tracks, just as many lives are decided by forces larger than themselves—economic needs, loss, isolation.

However, the railroad also represents a new world that demystifies his isolation, something he initially resists on some level. It’s important to note that while the film follows the same basic story as Denis Johnson’s novella, it reframes many of its ideas. For better or worse, nearly all of the unsavory behavior attributed to Johnson’s protagonist is removed. In the film, for example, Grainier witnesses a Chinese coworker being casually tossed off a bridge, and his tepid efforts to stop the injustice haunt him. In the book, Grainier himself participates in the act, and the coworker’s reappearance in his dreams is compared to a “curse” that ruins his life.

Another pivotal example is the scene where Grainier’s daughter may or may not return to him years after her disappearance. In the novel, she appears half-wolf when he finds her, a vision that resists straightforward interpretation and blurs the line between the mythic and psychological realism even further. When she “returns” in the film, injured and helpless but equally silent, it is all but confirmed as a dream—a fantasy that helps Grainier accept that his family isn’t coming back. Later, when he experiences wonder and amazement during his ride in the biplane and marvels at humanity’s landing on the Moon, he is embracing modernity—and a future he helped build.

Still, the film is perhaps best described as an elegy. For all intents and purposes, the Grainier we meet at the beginning dies with his family midway through the film. And yet the film’s most memorable line—“The dead tree is as important as the living one”—circles back around to the question of what it even means to live, anyway. Grainier experiences what most people would consider legitimate happiness for only a very short time, yet he looks back on his life with appreciation for his unique experience. Years of being alone didn’t make his somewhat fleeting connection to the world any less genuine.

To be frank, it is slightly awkward to end such an intensely bittersweet story with naked sentimentality. The line “he felt, at last, connected to it all” feels like the kind of conclusion that risks betraying the melancholic reality of everything we’ve just watched. This may be less an issue with the sentiment itself than with the narration, much of which feels superfluous—lifted directly from Johnson’s prose only to restate what the images already communicate. Ironically, that specific line is original to the film.

Regardless, Train Dreams remains a moving film about how there will never be enough time to forget the people we love, even across a lifetime of rebuilding. It’s one of the most memorable movies of the year. 12-21-25

Leave a comment